Use case 3: Coarse application isolation through Kubernetes Namespaces

Kubernetes Namespaces is a built-in means to “virtualise” Kubernetes clusters. While the jury is currently out regarding how and where to use Namespaces, cluster virtualisation can not be complete without the ability to isolate namespaces network-wise.

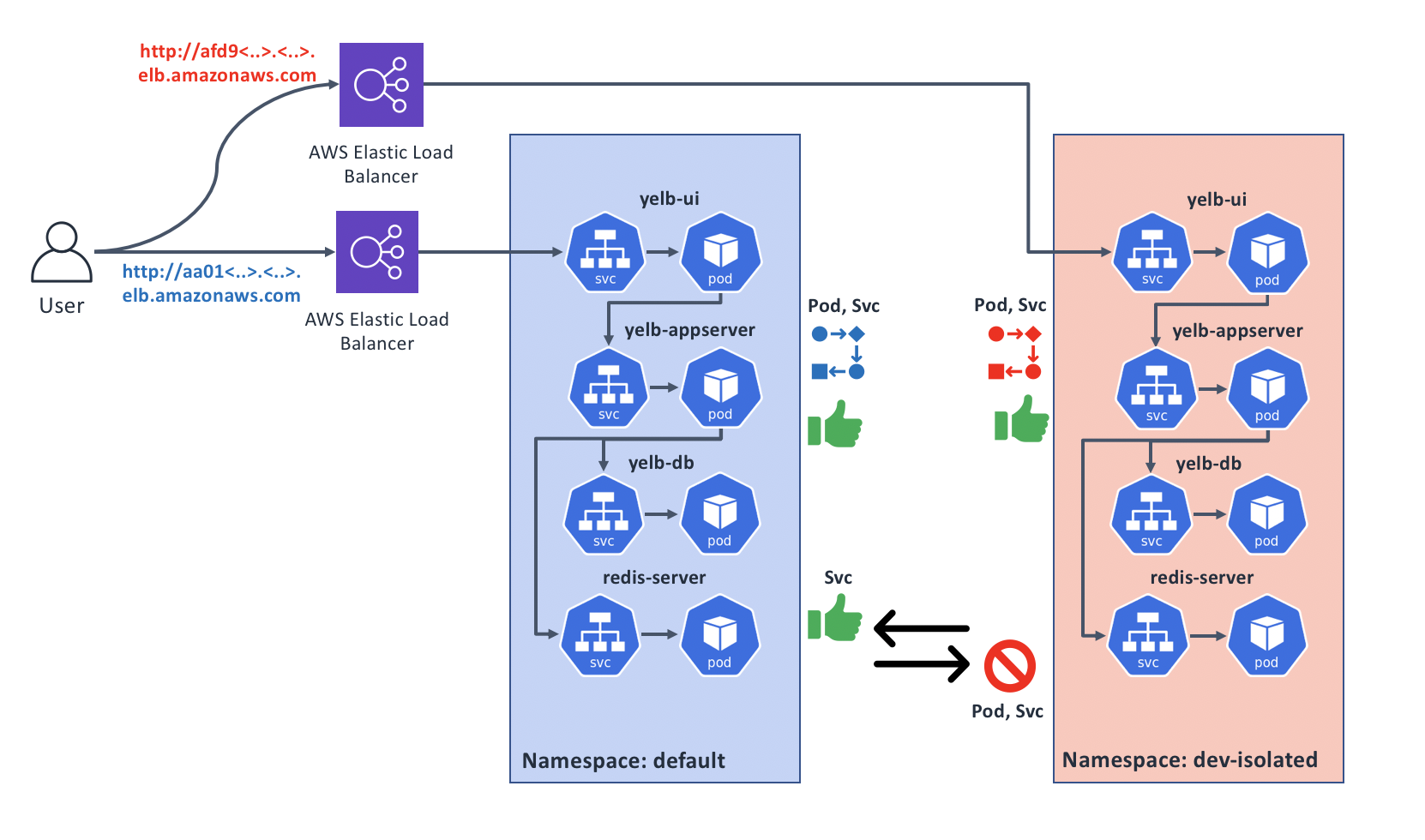

Tungsten Fabric Kubernetes CNI plugin includes support for isolated Namespaces. An application deployed into an isolated Namespace cannot reach any Pods outside the Namespace it’s in, and its Pods and Services cannot be reached by applications from other Namespaces.

When would I care?

One approach that organisations use is to deploy separate Kubernetes clusters per development team, in which case there’s little benefit to having cluster virtualisation and namespace separation.

However this approach may lead to inefficient use of resources, because unused capacity is fragmented. Each cluster has its own free capacity that cannot be used by applications running in other clusters. Additionally, as the number of clusters grows, it introduces operational overhead to keep things uniform. And last but not least, it takes time to bring up a new cluster, which may slow things down.

Namespaces are a good way to work around these problems as they help to reduce the number of clusters, share the spare capacity, and are quick to create. They can also provide a level of separation where an infrastructure team would look after the clusters, while individual developer teams operate within their own namespaces.

There are three general areas that need to be addressed when dealing with cluster virtualisation: (1) who can access the virtual cluster (RBAC); (2) how much compute resources each virtual cluster can use; and (3) what network communications are allowed for applications in virtual clusters.

Tungsten Fabric CNI plugin for Kubernetes is designed to help with the (3) through Namespace isolation that this section will talk about, and NetworkPolicy that is covered by the next section. This is especially useful from a regulatory compliance standpoint. PCI compliance is a great example, as it encourages workload isolation.

When looking to achieve PCI compliance, one of the key areas of focus is scope reduction. The goal of scope reduction is to isolate all systems which can affect the systems which process credit card information, known as the Cardholder Data Environment (CDE) in any way.

Any workload or device that can interact in any way with a system that is part of the CDE is considered in scope. Network segmentation is critical to achieving the isolation required to reduce the number of systems that would be considered in scope for PCI compliance purposes.

Kubernetes namespaces, and the underlying containerization platforms Kubernetes orchestrates, provide the compute isolation needed to reduce PCI scope for containerized workloads. Kubernetes also provides part of the solution regarding storage isolation, however, Kubernetes currently does not offer adequate network isolation or inspection for this purpose.

Tungsten Fabric CNI plugin for Kubernetes not only provides Kubernetes namespace-aware network isolation capabilities, it also provides operations teams the ability to inspect all network traffic in and out of a namespace by steering that traffic through Network Functions Virtualization (NFV) instances. This allows for the level of data flow inspection to be adjusted as required by the types of communication that must be allowed in and out of the isolated CDE.

Let’s explore an example of network isolation using Kubernetes namespaces. In this use case, we will deploy two copies of our sample app, one into the default Namespace, and one into a new isolated Namespace. We will then see how Tungsten Fabric enforces network communication isolation, as shown on this diagram:

Adding an isolated Namespace

Before jumping in, it’s worth to quickly scan Kubernetes documentation page that explains how to work with Namespaces, including commands we will need to know.

All done? Make sure you’re on the sandbox control node, logged in as root, and in the correct directory:

# Make sure we're root

whoami | grep root || sudo -s

# Change to the manifests directory

cd /home/centos/yelb/deployments/platformdeployment/Kubernetes/yaml

Next, let’s create a new manifest that describes our new isolated Namespace:

cat > dev-isolated.yaml <<EOF

apiVersion: v1

kind: Namespace

metadata:

name: "dev-isolated"

annotations: {

"opencontrail.org/isolation" : "true"

}

EOF

This should create a file called dev-isolated.yaml with the contents above. Note the annotations section - this is what will tell Tungsten Fabric to make your new Namespace isolated.

Go ahead to create this namespace and add a new context to Kubernetes config file so that we can access it:

# Create our new Namespace:

kubectl create -f dev-isolated.yaml

Let’s have a quick look at our new Namespace:

# kubectl describe ns dev-isolated

Name: dev-isolated

Labels: <none>

Annotations: opencontrail.org/isolation=true

Status: Active

No resource quota.

No resource limits.

Note the Annotations field; this signalled to Tungsten Fabric CNI plugin that it needs to treat this Namespace differently.

Could we have simply added this annotation to an existing Namespace to make it isolated? Unfortunately no, because Tungsten has to do a fair bit of additional work to set up a new Namespace as isolated. More specifically, if has to create a set of separate Virtual Networks that applications Pods in this Namespace will be connected to.

This ensures the network separation is maintained at a fundamental level, rather than simply through weaker methods like traffic filters.

Deploy sample app into an isolated Namespace

Next we will deploy our sample application into the isolated Namespace that we’ve created:

kubectl create --namespace dev-isolated -f cnawebapp-loadbalancer.yaml

Once the application pods are up, we should be able to access our application from the Internet same as described in Use case 1 above.

Next we’ll need something to compare and contrast with; so let’s deploy another copy of our sample app, but this time into the default Namespace:

kubectl create -f cnawebapp-loadbalancer.yaml

Now we have two copies of our app; one is running in the default Namespace that is not isolated, the other is in dev-isolated Namespace that is.

The behaviour that we expect:

- Pods and Services in non-isolated Namespace should be reachable from other Pods in non-isolated Namespaces (such as

defaultandkube-system) - Services in non-isolated Namespaces should be reachable from Pods running in isolated Namespaces

- Pods and Services in isolated Namespaces should only be reachable from Pods in the same Namespace

- Exception to the above: Services of type

LoadBalancerin isolated Namespaces will be reachable from the outside world.

Let’s validate this point by point.

Pods in non-isolated Namespaces should be able to talk

We know that Pods can talk to Services in our default namespace - that’s how our sample app works. But what about across namespaces? Since we’re in a sandbox, we could use one of Pods in kube-system namespace to try reach Pods and Services in our app that’s running in the non-isolated namespace default:

# Get the name of one of the kube-system pods; tiller-deploy:

src_pod=$(kubectl get pods --namespace kube-system | grep tiller | awk '{print $1}')

# Now let's get an IP of the "yelb-ui" pod in "default" namespace:

dst_pod_ip=$(kubectl get pods -o wide | grep yelb-ui | awk '{print $6}')

# Now let's ask tiller-deploy to ping yelb-ui:

kubectl exec --namespace kube-system -it ${src_pod} ping ${dst_pod_ip}

The last command should result in output similar to:

PING 10.47.255.246 (10.47.255.246): 56 data bytes

64 bytes from 10.47.255.246: seq=0 ttl=63 time=1.291 ms

64 bytes from 10.47.255.246: seq=1 ttl=63 time=0.576 ms

Cancel the command with ^C. This confirms that pods in non-isolated namespaces can reach each other.

Isolated Pods should be able to reach non-isolated Services

# Get the Cluster IP of the `yelb-ui` Service running in the `default` Namespace:

default_yelb_ui_ip=$(kubectl get svc --namespace default -o wide | grep yelb-ui | awk '{print $3'})

# Get the name of "yelb-appserver" Pod in the "dev-isolated" Namespace:

src_pod2=$(kubectl get pods --namespace dev-isolated | grep yelb-appserver | awk '{print $1}')

# Run "curl" on "yelb-appserver" trying to reach the Service IP in "default" Namespace:

kubectl exec -it -n dev-isolated ${src_pod2} -- /usr/bin/curl http://${default_yelb_ui_ip}

We should see ~10 lines of HTML code of our main yelb-ui page, which shows that a Pod in dev-isolated Namespace can talk to a Service in non-isolated default Namespace.

Pods in an isolated Namespace should not be reachable from other Namespaces

Now, let’s try to ping yelb-ui Pod that’s running in the dev-isolated Namespace from the same tiller-deploy Pod:

# Get an IP of the "yelb-ui" pod in "dev-isolated" namespace:

isolated_pod_ip=$(kubectl get pods --namespace dev-isolated -o wide | grep yelb-ui | awk '{print $6}')

# ..and try pinging it:

kubectl exec --namespace kube-system -it ${src_pod} ping ${isolated_pod_ip}

You should see that the command is “stuck”, not displaying any responses because this time we’re trying to reach something that isn’t reachable because Tungsten Fabric is preventing it.

Press ^C to cancel the command.

Experiment a bit more on your own - try pinging isolated yelb Pods and Services from yelb Pods in default Namespace. Is everything working as you expected it to?

LoadBalancer Services in isolated Namespaces should be accessible outside

It wouldn’t be much point to run application in an isolated Namespace if we couldn’t access it, though. Therefore, our copy of yelb that is running in an isolated Namespace dev-isolated should be available to the Internet through the LoadBalancer Service yelb-ui. Let’s test it:

kubectl get svc --namespace dev-isolated -o wide | grep yelb-ui | awk '{print $4}'

It should display something like afd9047c2915911e9b411026463a4a33-777914712.us-west-1.elb.amazonaws.com; point your browser to it and see if our application loads!

Cleanup

Once you’ve explored enough, feel free to clean things up:

# Delete the two copies of "yelb":

kubectl delete -f cnawebapp-loadbalancer.yaml

kubectl delete --namespace dev-isolated -f cnawebapp-loadbalancer.yaml

# Delete the isolated namespace and its Manifest:

kubectl delete -f dev-isolated.yaml

rm -f dev-isolated.yaml

Recap and what’s next

Kubernetes Namespaces have been designed as a means of virtualising Kubernetes clusters. No virtualisation is complete without networking, and Tungsten Fabric’s support for isolated Namespaces provides this function.

Isolated Namespaces however have low granularity that you may need when implementing application network security policies within your Namespace.

To get familiar with these more fine controls, check out the Use Case 4.